Changing our relationship with microscopic life

by Hari Byles and Ellie Doney

The Roving Microscope team (Melissa, Ellie and Hari) organise events aimed at shifting relations between humans and microbial life through offering different perspectives for engaging with soil ecology, and its vital role within wider ecosystems.

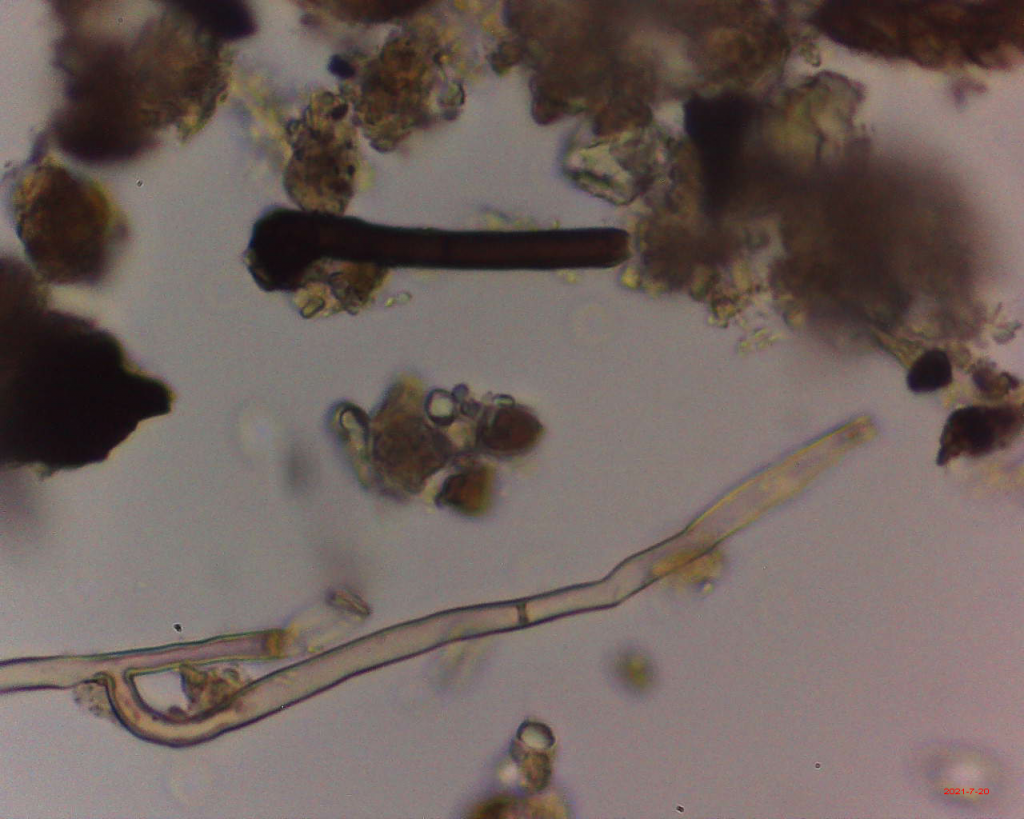

A key tool for doing this work is the use of a shared microscope which we have made available for public use outside of lab settings, in workshops and “microscopic lunches” that we organise in community gardens and kitchens. This enables audiences to go deeper into the microscopic worlds that they inhabit and which inhabit them, mediating new connections and affections between humans and non-humans.

Our microscope is part of a knotty web of multi-sensory tools, strategies, methods and creative knowledge practices that include video-making, co-drawing, foraging, cooking, close writing, painting billboards, fermenting and compost-making. All offer different entry points for relating to microscopic life:

“it is very exciting – something you’ve never imagined in a lump of soil, and it’s amazing to see that it’s alive actually… even if things move, people think it’s just the wind or something – it’s very much alive the whole thing… ”

(a previous Roving Microscope workshop participant)

Reflections on the MoTH workshop, activities & collaboration

We were invited to collaborate on organising and delivering a microscopic lunch as part of a research workshop about life and death in the soil food web at the Tower Hamlets Cemetery Park. We used some of our previous multi-sensory methods and tools, to investigate some of MoTH’s research questions, and contribute towards the project objectives to design new interspecies city services or infrastructures.

The first activity was a soil-food-web roleplay game in which participants were given info cards and identity stickers representing different members of the soil food web and a large ball of string. We threw the string between us and shouted across the field each time a connection was made, creating a beautifully knotty tangle of connections.

The graphic design of the cards and stickers helped people understand and visualise what for example, an arthropod or organic matter actually was. Even so, people weren’t quite sure, and there were lots of questions thrown out to the circle, which the group and facilitators attempted to answer together.

The second activity was a game of hide and seek. Participants were asked to mark out a small area anywhere in the cemetery with a piece of string, looking out for members of the soil-food-web and any interactions or relationships they could spot. They were also asked to collect soil samples or interesting objects for examination under the microscope. People enjoyed having time to stand and stare, which resulted in some original insights and observations about the soil-food-web and inhabitants of the cemetery (this bit probably could have gone on much longer).

“I was looking for Fungi. I couldn’t find any, but I did find a beer can, so …we were wondering about, you know, what would be detrimental to the environment there. Like, would the beer itself be ok? Would that provide sugar? Would that be acceptable or not? And then the can itself. We were talking about the fact that the paint finish of the can could be very damaging, the metal itself might rust into the soil. I saw some insects there. I saw some leaves there. And you know, that a leaf will take weeks or months to biodegrade compared to a beer can that would take possibly centuries, is quite striking contrast really. It would make a nice home for someone. And beer is a fungus! Yeast is a fungus. So I did find some fungus!”

(workshop participant)

Microscopic lunch, eating and looking together

We set up the projector so not everyone needed to look down the microscope and prepared samples of cheese and pond water for people to look at along with their soil samples and other finds. This enabled participants to visualise the microscopic inhabitants of the park that they would later be designing for.

The intention for this workshop was to bring together a wide ranging community to respond to the research questions, however this wider engagement was tricky given the constraints of the project, and many workshop participants came from academic backgrounds.

Non-academics in the group voiced some confusion, that they felt out of place or that their knowledge (of gardening or landwork) was not valued. This made us reflect on the role that academics and academic projects play in defining the questions and themes for projects like this, that are concerned with land, the future of urban space, and addressing injustice/exclusion. We have since wondered how this power/knowledge matrix could be distributed differently, so that wider communities are involved from the beginning in designing research which responds to their needs and interests.

In our group design session after lunch, we discussed the ways in which inequalities between humans are upheld by design interventions, consultations, and local decision-making processes. And suggested that, when addressing the deep inequalities between human and more-than-human interests in urban design, it also feels important to acknowledge and interrupt inequalities between humans.

How can we make new inventions which challenge these power imbalances; democratising, co-designing and commoning? Before driverless hedgehog buses and non-human members of parliament, perhaps we need to speculate about smart inventions for designing, thinking and dreaming together in ways which reroute and disrupt the systems of inequality which frame urban life?

We can do this in small ways too, through designing workshops that bring many different people together and give lots of space for emergent ideas, reflection and action. Reflecting on the fullness of these workshop activities, we wonder if the microscopic lunch would work well in future as a social “way in” to connecting with human and more-than-human life. For participants to gain a more detailed understanding of soil health, dedicated time and focus would be needed. Going forward, we want to prioritise time for workshop attendees to look through the microscope (if they want to), contribute their questions and perspectives to the discussion, connect with each other, challenge us and develop insights as agents in the activity.

Collaborating with the MoTH team on this project has helped us to gain new perspectives on our own methods and tools. It was exciting to be part of such a large project with so many creative and passionate thinkers. We also expanded our understanding of what ‘data’ can be, learnt about the tensions surrounding ‘smart cities’, and encountered some amazing creatures under the microscope we’d not met before.